California’s Sierra Nevada snowpack accounts for much of the water supply in many parts of the state. The snowpack retains large amounts of water in the winter that is then released as temperatures rise in the spring and summer. What is California’s Snowpack?

State Water Officials say ” Snowpack levels are presently at a depth of 185 in. recent storms have built up the Sierra snowpack levels across the state about 176% of normal compared to 149″ average depth for this time of year” with the deepest snowpack in Calif. at a depth of 259 inches.

The California Department of Water Resources’ electronic snow sensors throughout the state detected that the snowpack’s snow water equivalent is 44.7 inches, which is 190% above the average.

What is California’s Snowpack Today

The Department of Water Resources (DWR) today announced a significant boost in the forecasted State Water Project (SWP) deliveries this year due to continued winter storms in March and a massive Sierra snowpack.

DWR now expects to deliver 75 percent of requested water supplies, up from 35 percent announced in February. The increase translates to an additional 1.7 million acre-feet of water for the 29 public water agencies that serve 27 million Californians.

Consistent storms in late February and March have built up the Sierra snowpack to more than double the amount that California typically sees this time of year.

The Sierra snowpack, which hit its biggest level in 30 years earlier this month, is once again surging as forecasts suggest 3 fresh feet of snow may blanket large portions of the Central and Southern Sierra in the next three days.

On Tuesday 3/28/2023, the statewide snowpack stood at 217% of historical levels, up from 192% of normal last week.

The Southern Sierra has been particularly slammed by snowy weather this season, reaching 260% of normal snowpack levels on Tuesday. The Northern Sierra, meanwhile, reached 175% of normal, and the Central Sierra hit 223% of normal.

Rainfall has also allowed for robust flows through the system, providing adequate water supply for the environment and endangered fish species while allowing the SWP to pump the maximum amount of water allowed under state and federal permits into reservoir storage south of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta.

Before water flows through rivers, pipelines, and canals to cities and farms across the region, it starts as high-altitude snow. In fact, more than two-thirds of the river begins as snow in Colorado.

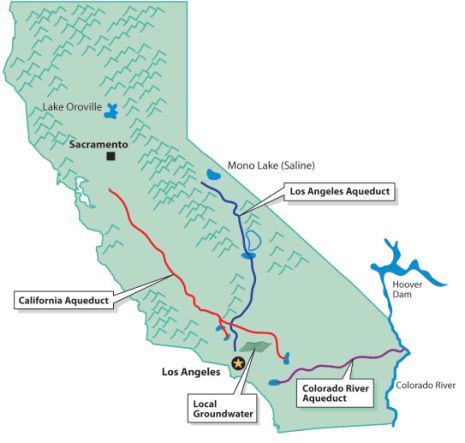

Separate from the California Aqueduct network is the Los Angeles Aqueduct, built and maintained by the LADWP. Unlike most of the water collected from the Sierras, the LA Aqueduct receives its water from runoff on the eastern side of the mountains. Here, it is seen with snowcapped Sierra Nevada Mountains in the background, carrying water to major urban areas of southern California

Snowmelt is the key to recharging streams, lakes, rivers, and reservoirs the combined layers of snow and ice on the ground at any one time were at their highest since 1995 for this point in the year. When it melts, the snowpack provides one-third of California’s freshwater supply.

The snowpack also keeps the Sierra soil moist by covering it longer into spring and summer. Soil moisture influences the onset of wildfires, as well as wildfire prevalence and severity. In addition, much of the hydroelectric power in California is reliant on water supplied by the melting snowpack.

*One acre-foot equals about 326,000 gallons or enough water to cover an acre of land, about the size of a football field, one foot deep. An average California household uses between one-half and one acre-foot of water per year for indoor and outdoor use.

Current Snow Depth Map

California receives about 193 million acre-feet of water each year as precipitation (rain and snow), but there is great variability between regions. Yearly precipitation on the North Coast is about 90 inches but only 2 inches in Death Valley.

As of January 20, the Sierra snowpack state-wide was at 240 percent of the average for this time of year. The South Sierra stations, located between the San Joaquin and Mono counties through to Kern County, reported snowpacks at 283 percent of the January 20 average.

The Sierra Nevada snowpack usually peaks around April 1. Currently, state-wide, the snowpack is at 126 percent of the average for April 1, with the South Sierras in particular at 149 percent. When it melts, the snowpack provides up to one-third of California’s freshwater supply.

Snowmass in Colorado the snowpack is 130% of the average for this time of the year. The Roaring Fork watershed, which includes Aspen and Snowmass, makes up only 0.5% of the landmass in the Colorado River Basin but provides about 10% of its water for the Colorado River. Still, Snow piled high in the Rockies is critical for the Colorado River

In other nearby mountain ranges, snow totals are between 140% and 160% above average. Even if those numbers persist until spring, the severity of the Colorado River’s drought means many more years of heavy snow are needed to make a serious dent in the low water levels.

Strong storms and cold temperatures are the right ingredients for a deep snowpack in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, which provides water for about 23 million Californians from the Bay Area to Southern California

The California Aqueducts

The California Aqueduct, in full Governor Edmund G. Brown California Aqueduct, is the principal water-

The California Aqueduct, in full Governor Edmund G. Brown California Aqueduct, is the principal water- conveyance structure of the California State Water Project, U.S., and one of the largest aqueduct systems in the world.

conveyance structure of the California State Water Project, U.S., and one of the largest aqueduct systems in the world.

The California State Water Project, begun in 1960, is designed to transport water to arid southern California from sources in the wetter northern portion of the state.

The California Aqueduct conveys water about (705 miles) across the state of California, yielding more than(650 million gallons) of water a day. It serves some 27 million people and 750,000 acres of farmland.

Strong storms and cold temperatures are the right ingredients for a deep snowpack in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, which provides water for about 23 million Californians from the Bay Area to Southern California.

So how does all that water actually travel hundreds of miles through the Bay Area and Central Valley to Southern California?

The Los Angeles Aqueduct system, comprising the Los Angeles Aqueduct (Owens Valley aqueduct) and the Second Los Angeles Aqueduct, is a water conveyance system, built and operated by the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power.

The Colorado Aqueduct- The Colorado River Aqueduct is a 242 mi water conveyance in Southern California operated by the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California. The aqueduct takes and holds water from the Colorado River at Lake Havasu on the California-Arizona border, west across the Mojave and Colorado deserts to the east side of the Santa Ana Mountains. It is one of the primary sources of drinking water for Southern California.

Sierra Snowpack Harvesting

When air temperatures begin to warm in the spring, snow that has accumulated over the winter in California’s Sierra Nevada melts, releasing water as runoff. This runoff provides about one-third of the state’s annual supply for agriculture and urban needs. Over the past century, a greater proportion of runoff from the Sierra Nevada has been flowing into the Sacramento River earlier in the spring.

The volume and timing of snowmelt runoff are affected by the air temperature. During the winter, warmer temperatures mean that less precipitation falls as snow than as rain, resulting in less snowpack. The earlier arrival of warmer temperatures in the spring causes snow to melt earlier in the year.

Spring runoff supplies Californians with water for domestic and agricultural uses, hydroelectric power generation, and recreation. Reduced runoff affects ecosystems, stressing vegetation and habitats for certain fish. Increased tree deaths and wildfires have also been linked to declining snowmelt. Tracking trends in spring snowmelt runoff is critical to understanding how runoff is affected by a changing climate.

California’s water management and flood protection strategies rely on capturing and storing runoff for delivery during the drier summer and fall months. Water managers track spring runoff as a key consideration in planning to meet the state’s water supply needs. The state’s water infrastructure was built based on historical patterns of precipitation and runoff. As the climate continues to change, these patterns are no longer the norm, calling for changes to existing water storage and flood management practices.

JimGalloway Author/Editor

References:

Water Education Foundation- What is an Acre-Foot

NOAA- Snowpack + Snowmelt = Water